Discussing Police Officers' Perceptions on Citizens' Attitudes

Introduction

Police

officers’ perceptions about citizen demeanor is essential in understanding the

use of discretion in police-citizen interactions. Many assumptions exist about this topic and

distort the reality of the events that cause police officers to perform

citations, arrests, or other mechanisms that they have the authority to

deliver. Specifically, many claims about

racial and ethnic biases and unnecessary interventions exist in these

interactions between police officers and civilians (Engel, Klahm, &

Tillyer, 2010; Engel, Tillyer, Klahm, & Frank, 2012). However, there is a large body of literature

that infers that police officers’ perceptions about citizen demeanor during

encounters is the main variable for the type of discretion that is used (Engel et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger, 1994;

Worden & Shepard, 1996).

Interestingly, the demeanor concept has many variations from police

officer-to-police officer and can even change again when citizens explain their

understanding of appropriate behavior while interacting with police officers (Engel

et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden & Shepard, 1996). Thus, the conundrum of what definition is

correct comes about. Nonetheless, the

perception of demeanor by police officers has more importance in social science

research because they are the party that is given the authority to make a

decision about what conduct is inappropriate and, in turn, requires a

particular administration of law enforcement.

Given this dilemma, this essay will summarize numerous academic writings

on police officers’ perceptions about citizen demeanor and the use of

discretion based on these perceptions to generate better understandings about

the content.

Summary

of Literature

Social

science research on this topic has repeatedly shown that there is a host of legal

and extra-legal factors that contribute to arrests and other applications of

law during encounters with police officers (Engel et al., 2010; Engel et al.,

2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden & Shepard, 1996). Claims of racial and ethnic biases, as well

as other alleged prejudices, has, for the most part, guided the purposes of

studying the decision-making processes in police work (Engel et al., 2010;

Engel et al., 2012). These allegations

have been traced back to the history of treatment toward minorities in the United

States in general and specifically by the hands of police departments, as well

as claims by civilians about police misconduct not pertaining to racial and

ethnic prejudices (Engel et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2012).

With

this being stated, there have been studies that show disproportionate arrests when

minorities interact with police officers, yet there are, again, many legal and

extra-legal factors that contribute to arresting an individual during these

police-citizen events that fail to be considered by laypeople (Engel et al.,

2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden & Shepard, 1996). First, the legal factors will be discussed in

their full breadth. That is, many

arrests that occur during police-related situations happen because of illegal

actions or previous illegal actions by citizens (Engel et al., 2010; Engel et

al., 2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden & Shepard, 1996). Contraband, warrants, disorderly conduct, and

any other unlawful activities by civilians are the major legal factors that

contribute to an arrest during encounters with police officers (Engel et al.,

2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden & Shepard, 1996). Research and arrest statistics validate this

but, in many cases, only present simplistic data of the illegalities that were

discovered by police officers and characteristics of the arrestees. So, even if there are disproportionate

numbers regarding minority arrests, the sheer fact that illegalities exist can circumvent

many claims about biases. Second, and

more important, extra-legal factors guide the use of arrest during encounters

with civilians more profusely (Engel et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger,

1994; Worden & Shepard, 1996).

Engel, Klahm, and Tillyer (2010) discussed how police officers’

perceptions about civilian conduct is the primary catalyst in determining

whether a person should be arrested during a traffic stop. More specifically, these scholars used data

from a prominent study in Cleveland, Ohio to merit their postulations (Engel et

al., 2010). Data from this study

confirmed that officers’ perceptions about disrespect being displayed toward

them resulted in a higher likelihood of arrest (Engel et al., 2010). Furthermore, interactions that entailed resentment,

anger, hostility, verbal and physical force and abuse resulted in police

officers making arrests during traffic stops more often than other forms of

disrespect (Engel et al., 2010). The

findings also indicated that race and ethnicity did not have a significant

influence on drivers’ arrest when other legal and extra-legal factors were

controlled for (Engel et al., 2010, p. 298).

In

a unique contrasting notion, Klinger (1994) questioned the operationalization of

citizen demeanor in previous studies by using three key factors that he felt had

been overlooked. First, he pointed to

how demeanor has been improperly defined as criminal behaviors in many studies

in general, which in turn means that previous studies failed to properly define

and separate citizen demeanor and illegal behavior (Klinger, 1994). Second, Klinger (1994) posited how many

previous studies failed to control for criminal behaviors during interactions

with police officers and, as he infers, that citizen demeanor was not properly

defined or controlled for as well.

Lastly, Klinger (1994) stated that measures of criminal behavior have

been so imprecise in previous studies that it has created a serious flaw in the

specific research subject. This notion

about misguided research by Klinger (1994) caused many social scientists to

reexamine their measures on police officers’ decisions to arrest (Engel et al.,

2012; Worden & Shepard, 1996). In

his words, “…the manner in which previous observational police research

controlled for crime may have consequences beyond the demeanor issue. It raises the prospect that all reports of

independent extralegal effects may misrepresent the nature of the relationship

between the particular factor and arrest” (Klinger, 1994, p. 491). Given the desired accuracy in academic

research, it is proper to pose this inquiry when examining police officers’

perceptions about behaviors that are deemed worthy of arrest.

Because

of this, researchers began to reexamine studies and be more precise during

their analyses. Worden and Shepard

(1996) did exactly this and also criticized Klinger (1994) for his dissent

toward previous research agendas on demeanor and police use of discretion. They suggested that the operationalization

was not as problematic as Klinger (1994) presented because of the variations in

analyses on demeanor and other variables in this subject (Worden & Shepard,

1996). Basically, the idea that a

general claim about particularities associated with measurements on demeanor

during police-citizen encounters was not valid according to Worden and Shepard

(1996). They also confirmed the idea

that controls for demeanor were done according to the specifics in many

examinations on the subject (Worden & Shepard, 1996). Thus, discrediting Klinger’s (1994) scrutiny

and putting faith back into the previous research on the topic of citizen

demeanor and arrests by police officers.

Since

the validity of demeanor measurement had been questioned, more detailed

research methods were undertaken by social scientist examining the

subject. Engel, Tillyer, Klahm, and

Frank (2012) also recognized the issues presented by Klinger (1994) and decided

to embark on a study that attempted to resolve the quandaries about measuring

demeanor. Traffic stops and civilian

demeanor during these encounters were again measured to comprehend how perceptions

of demeanor by police officers influenced the administrations of justice (Engel

et al., 2012). Even though these authors

went to great lengths to define various types of demeanor and, in turn,

performed advanced research methods to determine correlations, they still

discussed the difficulties in properly defining it and went on to say that it

is vital to attempt to understand the onset of specific demeanors by citizens

when interacting with police officers (Engel et al., 2012). This conclusion brought a new insight into

the studying of demeanor and police-citizen encounters. Elaborating more, researchers began to

measure the reasons why citizen demeanors came about, as well as the

perceptions of the demeanors by police officers with specific situations in

mind.

Conclusion

In

sum, research on demeanor during police-citizen encounters has produced mixed

results (Engel et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden &

Shepard, 1996). Some scholars have

inferred that the majority of measurements on demeanor are appropriate due to

the specifics of the studied being performed, while others have posited that

more in-depth explorations about the reasons for the onset of demeanors should

take place (Engel et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden &

Shepard, 1996). Although the

discrepancies are evident, the body of research about police officers’

perceptions on citizen demeanor suggests that behavior that is viewed as

disrespectful or inappropriate has a higher likelihood to result in an arrest (Engel

et al., 2010; Engel et al., 2012; Klinger, 1994; Worden & Shepard, 1996).

References

Engel, R. S.,

Klahm, C. F., & Tillyer, R.

(2010). Citizens’ demeanor, race,

and traffic stops. In

S. K. Rice & M. D. White (Eds.),

Race, ethnicity, and policing: New and essential

readings

(pp. 287-308). New York, NY: New York University Press.

Engel, R. S.,

Klahm, C. F., Tillyer, R., & Frank, J.

(2012). From the officer’s perspective:

A

multilevel examination of citizens’ demeanor during traffic stops. Justice

Quarterly,

29(5), 650-683.

Klinger, D.

A. (1994). Demeanor or crime? Why "hostile" citizens are more likely

to be

arrested. Criminology,

32(3), 475-493.

Worden, R. E.,

& Shepard, R. L. (1996). Demeanor, crime, and police behavior: A

reexamination of the police services

study data. Criminology, 34(1), 83-105.

|

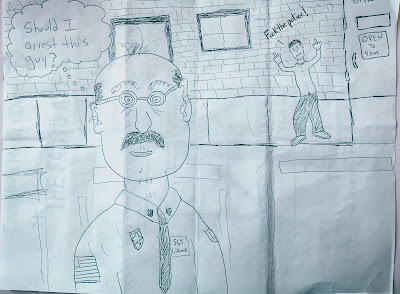

| Photo Credit: Benjamin Bolton |

Comments

Post a Comment